Coming fresh out of yet another client meeting about which number to use as a consistent well ID, I have something to get off my chest.

API numbers are useful for many things, but they make LOUSY corporate Well ID’s.

Three reasons:

- Formatting

- Inconsistent availability

- Shifting meanings by discipline

We’ll walk through why these are such problems when trying to use API (American Petroleum Institute) number as a corporate Well ID. We’ve proposed one potential solution to these issues before – for most companies, the ID used in a system like Reserves or Accounting is a better choice. Let’s dive in!

Formatting

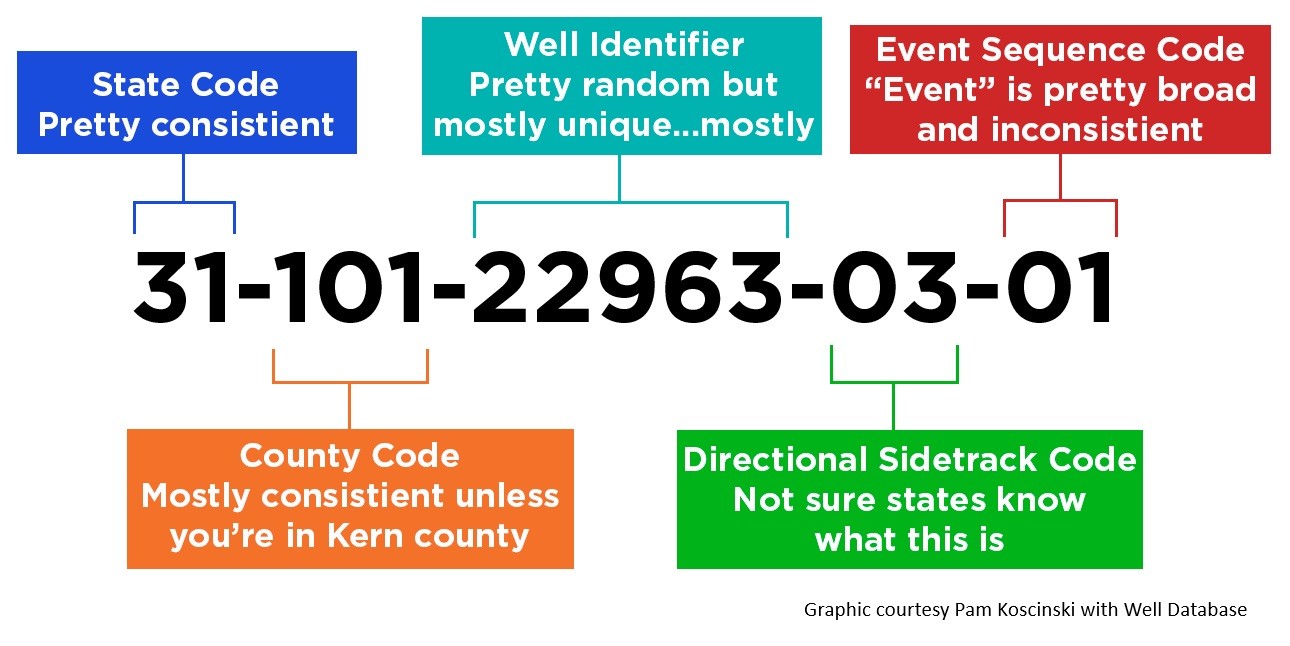

Veterans of O&G data work will nod their heads at this – API number formatting is a hot mess. Are we talking about 10 digit or 14 digit? US standards or international? Dashes or no dashes? Is it a number data field, or a text field? If I see another API number that Excel interprets as “4.2E+13” I’m going to drive a stake through someone’s eyeball.

Formatting matters, because computers are linear thinkers. If I ask a computer “Does ‘ABC’=’a-b-c’?”, it’s usually going to say “Heck no, those are obviously different!” 42-003-12345 doesn’t equal 4200312345, and it certainly doesn’t equal 42-003-12345-0001 or 42003123450000. A savvy O&G data person knows intuitively that all four of those are probably the same well in Andrews County, Texas. In order for a computer to know that, it would have to use lots of complex, branched logic that is expensive to build and maintain. (Come at me with your LLM’s on another day.)

But dashes and 10-digit vs 14-digit are just the start – is it a number or a text field? I recall seeing a reserves report a few years ago with API numbers formatted like “4,200,312,345.00”. I’m not sure whether that API number should make you laugh, or cry. Text data types generally work better: just imagine what happens in Colorado – if you format your API number as a number data type, it will often turn from 0512312345 (as text with the leading zero) to 512312345 (as number without the leading zero). Boom, you can’t match between systems without a lot of fancy logic.

Inconsistent Availability

Since API numbers are created by regulatory authorities, not all wells have API numbers. Heck, Virginia didn’t start using the system until 2014! Even in states that did assign APIs when the well was drilled, if a well doesn’t exist in the state records (such as pre-1967 wells), it probably doesn’t have a clean API number. Pam Koscinski wrote a fantastic blog series for Well DataBase. It’s a must-read for anyone working with older wells.

Pam documents some fascinating specific state-by-state issues, like Oklahoma’s use of letters to mark regulatory events and the absolutely bizarre way that Kentucky has (mis)used API numbers over the years.

But even if your state is pretty clean and you don’t care about anything pre-1967, what do you do about undrilled wells? PUD’s (proved undeveloped wells) usually don’t have an API number available, but they are important to keep track of in systems like Accounting, Land, and Reserves. How should you assign them API numbers?

The idea of using API number as a universal connector is a great one, but the reality is that for proprietary datasets inside of a company, many “wells” simply don’t have an API number available.

Shifting Meanings By Discipline

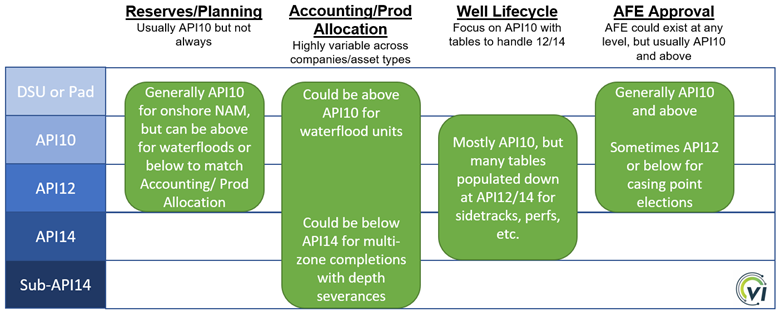

The final nail in the coffin for using API as a corporate well ID is the fact that depending on your discipline, the meaning of a “well” changes or even loses its meaning entirely.

While a well in the drilling world is pretty straightforward (one wellhead = one well), other disciplines don’t think that way. Imagine a production engineer working a field with 20 producers coming into a single battery. Production optimization is often done by looking at the total battery production. Allocations to individual wells are just that – an allocation with a host of assumptions that may or may not be reliable.

To keep going, imagine an accountant booking costs to a waterflood at the unit level, or a landman dealing with heavily depth-severed leases. While “wells” are certainly involved in their workflows, they aren’t the essential entity.

I built this diagram as a part of a client project last year – it’s a representation of a typical set of data conundrums. API number can’t resolve issues it doesn’t cover, and lots of “wells” aren’t easily addressed by something like an API10. Note that this diagram is focused on onshore North American use cases, but you could draw similar diagrams (with similar problems) in international and offshore plays.

Summary

If all I’ve done here is complain, that was kind of the intent. API number is irreplaceably useful if you’re looking at public datasets that are consistently at a well level, but it has huge limitations if you try to use it as a corporate well ID.

Give us a shout if you want to chat about some better approaches!

One extra note: these blog posts are always a team effort, but this one was even more than usual. Huge thanks to Pam Koscinski for her great work over the years, plus Haley Busche, Michael Hirsch, Andrea Switzer, and Clint Vallandingham on the VI team. This blog post would have been much less clear without your help!